Taylor

Good evening Norris, I am Taylor, and this is Goose Pod for you. Today is Monday, December 08th, and the time is 22:14. We have a fascinating narrative unfolding in the aerospace sector today that feels like a major plot twist in a long-running drama.

Donald

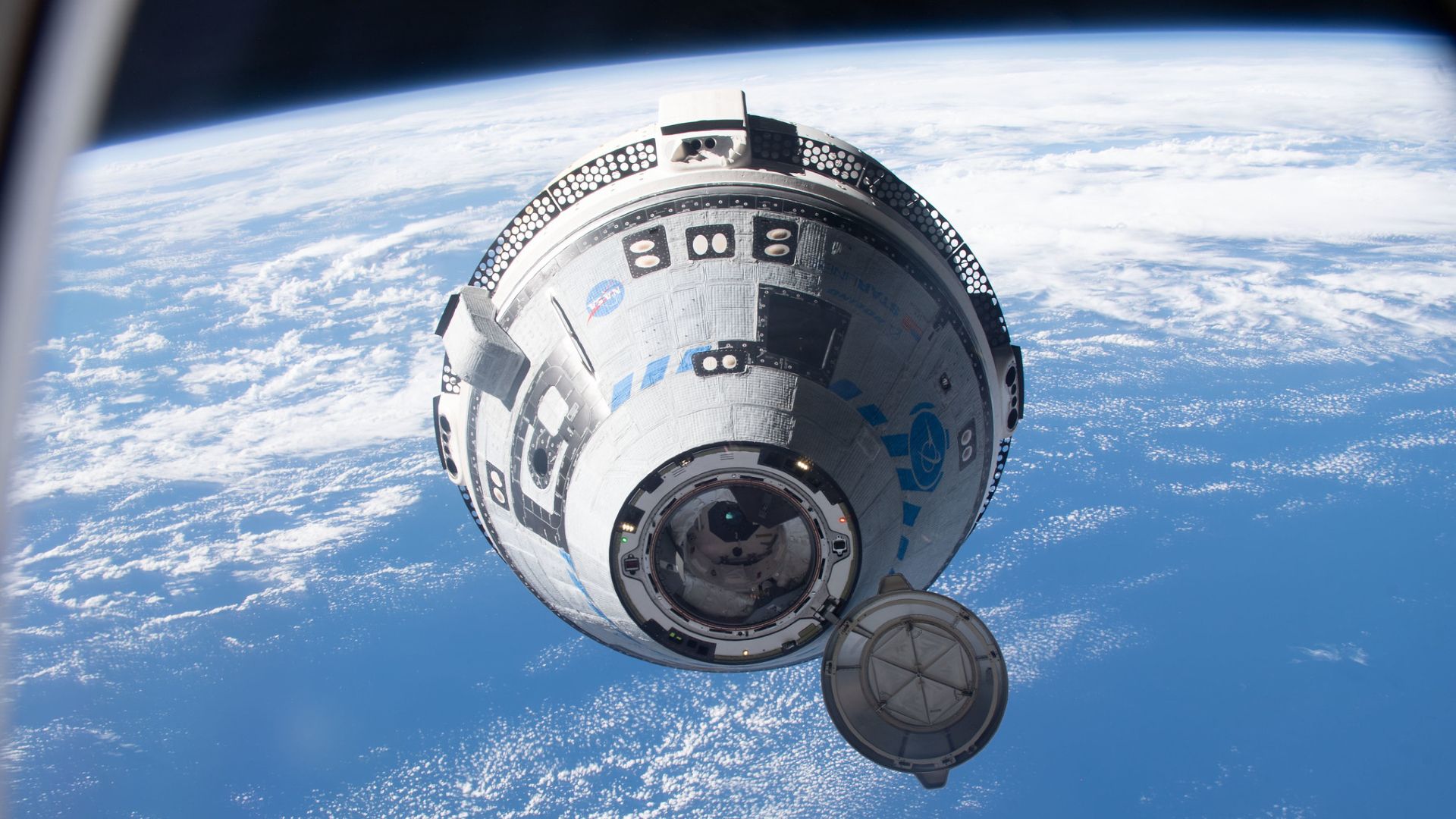

And I am Donald. We are here to talk about a disaster, folks. A total mess. We are discussing Boeing’s next Starliner spacecraft, which won't carry any NASA astronauts when it launches in April 2026. Empty seats, Norris. Can you believe it?

Taylor

It is a significant development, Norris. NASA has officially announced that the next Starliner mission, currently targeted for no earlier than April 2026, will be a cargo-only flight. They are effectively downgrading the mission profile from a crewed flight to a supply run, which tells us a lot about their current risk assessment.

Donald

They are scared to put people on it, and rightfully so. You look at what happened before, it was a catastrophe. They had a mission in 2024, the Crew Flight Test, and it was supposed to be a quick trip. A nice little vacation to the space station.

Taylor

That is the critical context here. The Crew Flight Test 1 in June 2024 launched with two veteran NASA astronauts, Butch Wilmore and Sunita Williams. The narrative hook is that they were only supposed to be there for about eight to ten days. It was a test run to prove the system worked.

Donald

Eight days turned into eight months, Norris! Imagine that. You pack for a week and you get stuck there for almost a year. Why? Because the machine broke. The thrusters failed. The helium leaked. It was falling apart up there. They couldn't bring them home.

Taylor

Exactly, and that specific failure is driving this new decision. The thruster system concerns were so severe that the Starliner capsule returned to Earth autonomously, without the crew. Butch and Suni had to wait for a ride home on a SpaceX Dragon spacecraft. It created this incredible juxtaposition of the old guard failing and the new competitor stepping in.

Donald

It is humiliation, pure and simple. Boeing, this massive company, they take the money, billions of dollars, and they leave our astronauts stranded. And who has to save them? Elon. SpaceX. They had to hitch a ride with the competition. It makes Boeing look very, very weak.

Taylor

So now, looking ahead to 2026, NASA and Boeing have agreed to modify the contract. They are reducing the number of guaranteed crewed flights. Originally, the contract from 2014 stipulated six operational missions. Now, they have cut that down to four, with the remaining two just being options.

Donald

They are cutting the order because the product doesn't work. It is that simple. You don't keep buying cars that lose their wheels on the highway. NASA is saying, look, prove you can fly without killing anyone, then maybe we talk about the rest. It is a bad deal for the taxpayer.

Taylor

The focus now is entirely on certification. This modification allows them to use the 2026 flight to rigorously test the propulsion system again, without risking human life. They need to prove the system is safe before they can even think about executing that first operational crew rotation.

Donald

They have been trying to prove it is safe for ten years, Taylor. Ten years! And they still need another test flight in 2026? It is unbelievable. We are talking about a program that is billions over budget and years late. It is a masterclass in how not to do business.

Taylor

To understand how we reached this point, Norris, we have to look at the backstory. This all started back in 2011 and 2014 with the Commercial Crew Program. The strategy was brilliant on paper: NASA wanted to stop building the taxis and start buying the tickets. They wanted private industry to handle low-Earth orbit transport.

Donald

They gave out two big contracts. One to SpaceX, and one to Boeing. And everybody thought Boeing was the sure thing. They said, oh, Boeing has been building planes forever, they know what they are doing. SpaceX was the wild card. But look at where we are now.

Taylor

That is the irony of this arc. Boeing received the larger contract, $4.2 billion, compared to SpaceX's $2.6 billion. The narrative expectation was that the legacy aerospace giant would lead the way. But the Starliner program has been plagued by what I call 'gremlins in the machine'—persistent technical glitches.

Donald

It is not just gremlins, it is incompetence. In 2019, they had a test flight that failed to even reach the station. The clock was wrong! The software timer was off. How do you spend billions and get the time wrong? Then they had to redo it in 2022. Delay after delay.

Taylor

Those delays have compounded. While Boeing was troubleshooting software glitches and valve issues, SpaceX began regular operational service in 2020. They have been running a shuttle service to the ISS for years now. This contrast highlights Boeing's struggles even more sharply. The 2019 failure was a 'high-visibility close call,' according to NASA.

Donald

And it is costing them a fortune. Boeing is bleeding money on this. We are talking about $1.85 billion in losses. And because it is a fixed-price contract, the taxpayer isn't paying for the mistakes, Boeing is. At least the contract was written right in that regard. They eat the loss.

Taylor

That fixed-price structure is a key plot point. In the old days, cost-plus contracts meant companies got paid more when they made mistakes. This new model forces accountability. Kelly Ortberg, the new Boeing CEO, has openly admitted they signed up for some problematic things. They are stuck in a deal that is draining their resources.

Donald

He knows it is a bad deal. He is looking at the books and saying, what is this? But they can't just walk away. They are Boeing. If they walk away from NASA, they look like quitters. But they are losing $250 million here, $100 million there. It adds up to real money, folks.

Taylor

And we must remember the technical specifics that caused this latest setback. It wasn't just one thing. It was a combination of five failed thrusters and multiple helium leaks. The propulsion system, specifically the reaction control thrusters, had issues with Teflon seals expanding under heat. It is a detailed engineering failure.

Donald

Teflon seals expanding. It sounds like bad plumbing. You expect better engineering from a company that builds jetliners. But this is what happens when you lose your edge. They got comfortable, they got lazy, and the competition ate their lunch. Now they are playing catch-up.

Taylor

The timeline is also compressing. The ISS is not going to be there forever. NASA plans to retire the station in 2030, deorbiting it into the Pacific Ocean at Point Nemo. This gives Boeing a very narrow window to actually fulfill their contract and get some return on this investment.

Donald

Point Nemo. A watery grave. That is where the space station is going, and frankly, that is where this Starliner program might be heading if they don't fix it fast. They have four years left until the station is gone. Tick tock, Boeing. The clock is running out.

Taylor

The conflict here is palpable, Norris. You have the clash between NASA's desperate need for redundancy and the reality of Boeing's technical failures. NASA does not want to rely solely on SpaceX. It is a strategic risk to have a monopoly on access to space. They need Starliner to work.

Donald

They are begging for it to work. They are bending over backwards. But look at the optics. You have two American heroes, Butch and Suni, who were stranded. The media called them 'stranded.' NASA hated that word, but that is what they were. They were stuck in orbit because the car wouldn't start.

Taylor

And the resolution to that specific conflict was the SpaceX rescue. Bringing them home on a Dragon capsule in 2025 was a narrative climax that no one at Boeing wanted. It visually cemented SpaceX's dominance. The empty Starliner seat returning to Earth was a powerful symbol of that failure.

Donald

It was a total surrender. They had to admit their ship wasn't safe. Imagine the conversation in the boardroom. 'We have to ask Elon for a ride.' It must have been painful. And the shareholders are furious. The stock is taking a hit, the reputation is in the toilet.

Taylor

There is also the internal conflict at Boeing. They are dealing with broader issues in their aviation division, and now their space division is becoming a liability. The analysts are questioning if they should even stay in the space business. It creates a tension between their legacy and their financial reality.

Donald

They should have focused on quality. They lost their way. They were too busy trying to be politically correct or whatever they were doing, and they forgot how to build rockets that work. Now they are cutting the contract from six flights to four. That is an admission of defeat.

Taylor

That reduction in flights is significant. It is a mutual agreement, but it reads like a vote of no confidence. By making the last two flights optional, NASA is essentially saying, 'We will see how you do on the first few before we commit to the rest.' It changes the power dynamic completely.

Donald

It saves the government money, about $500 million they say. That is good. We shouldn't be paying for flights that might never happen. But it leaves Boeing with a lot of sunk costs. They spent the money to develop a system for six flights, and now they might only fly four. Bad math.

Taylor

The impact of this decision extends beyond just the ledger, Norris. For the astronauts, it means uncertainty. The rotation schedule for the ISS is a complex dance. When Starliner gets delayed or downgraded to cargo, it forces NASA to reshuffle crews, extend missions, and lean harder on SpaceX.

Donald

SpaceX is carrying the whole country on its back right now. If something happens to the Dragon capsule, God forbid, we have zero way to get our people to the station. Zero. That is a dangerous position to be in. We have no backup plan because the backup plan is broken.

Taylor

This is why the 2026 certification is so critical. It is not just about fulfilling a contract; it is about restoring that second lane to low-Earth orbit. If Starliner can't be certified in 2026, we are looking at a scenario where the ISS might retire without Boeing ever flying a full operational rotation.

Donald

And think about the prestige. America is supposed to be the leader. We are supposed to be number one. But we have one company doing everything and the other legendary company stumbling around. It looks bad on the world stage. We need strength, and right now Boeing is showing weakness.

Taylor

There is also a downstream impact on the future of commercial space stations. Companies like Blue Origin and others are planning stations to replace the ISS. They were counting on having multiple transport providers. If Starliner exits the stage, the economics of those future stations become more complicated.

Donald

They will just use SpaceX. Everyone will just use SpaceX. Unless Boeing wakes up. Kelly Ortberg has a tough job. He has to decide if he wants to throw more good money after bad. Personally, I like winners. And right now, this program is not winning.

Taylor

Looking to the future, Norris, the next major plot point is April 2026. That uncrewed flight is make-or-break. If the thrusters perform and the helium stays inside the tanks, they might salvage the program. They could fly crew by 2027. It is a redemption arc waiting to happen.

Donald

I have my doubts. They have had years to fix these valves and seals. If they haven't fixed it by now, why will they fix it by 2026? But we will see. Maybe they pull a rabbit out of the hat. But I wouldn't bet your money on it, Norris.

Taylor

And ultimately, the clock stops at 2030. When the ISS deorbits, this chapter closes. Whether Starliner flies four times or zero times, the era of the ISS is ending. The industry is shifting toward lunar missions and Mars. Boeing risks being left behind in low-Earth orbit history.

Taylor

That is the end of today's discussion. Thank you for listening to Goose Pod. It is a story of ambition, failure, and the relentless march of technology. We will be watching 2026 very closely. See you tomorrow.

Donald

Goodbye Norris. Let's hope they get their act together. We need to win in space. Thanks for listening to Goose Pod. Have a great night.