## Hollywood's AI Civil War: The Transformative, Disruptive, and Contentious Rise of Machine-Generated Cinema **Report Provider:** The Hollywood Reporter **Author:** Steven Zeitchik **Publication Date:** July 16, 2025 This report delves into the burgeoning "AI insurgency" within Hollywood, exploring how artificial intelligence is rapidly transforming filmmaking, from content creation to production economics, and sparking a significant debate about the future of artistry, labor, and the very essence of cinema. ### Key Findings and Conclusions: * **AI is Already Embedded in Filmmaking:** AI tools are no longer a futuristic concept but are actively being integrated into various aspects of film production, from generating visual effects and imagery to conceptualizing scenes. Companies like Asteria, Runway AI, and Luma AI are at the forefront of this movement. * **Dual Nature of AI: Creative Tool vs. Existential Threat:** AI is presented as a powerful tool that can democratize filmmaking, enabling independent creators to achieve studio-level output and allowing established filmmakers to explore new creative avenues with reduced costs and increased speed. However, it also poses significant risks to artistic integrity, labor, and the established economic models of Hollywood. * **The "Civil War" of AI in Hollywood:** A clear divide exists between proponents of AI, who see it as an evolutionary step akin to the advent of CGI or the internet, and critics who fear it will lead to a homogenization of art, job displacement, and a devaluation of human creativity. * **Copyright and Ethical Concerns:** Major studios like Disney and Universal are initiating legal battles against AI companies like Midjourney, alleging copyright infringement due to the models being trained on vast amounts of existing film and image data without compensation or credit to the original creators. This legal landscape is crucial in determining the future of traditional production models. * **Economic Implications: Cost Savings vs. Business Model Disruption:** While AI promises significant cost savings, potentially halving the expense of effects-heavy films, studio executives are also wary of the long-term implications, including the possibility of consumers generating their own content, thereby undermining the traditional studio business model. * **The Human Element: Artistry vs. Efficiency:** A central debate revolves around whether AI can replicate or enhance human creativity. Proponents like Asteria co-founder Bryn Mooser believe AI can help filmmakers "crack the code" of new creative possibilities, while critics like Justine Bateman argue that AI-generated content is merely a "regurgitation of the past" that lacks the human ingenuity and problem-solving that defines great cinema. ### Significant Trends and Changes: * **Democratization of Production:** AI tools are empowering smaller studios and independent filmmakers to produce content with a scope previously only achievable by major studios. * **New Forms of Storytelling:** AI is enabling the creation of entirely new genres and visual styles, such as "digital humans" and AI-driven creatures that can bypass traditional labor guilds. * **Shift in Production Workflow:** The process of filmmaking is shifting from physical sets to digital control rooms, with AI tools allowing for rapid iteration and manipulation of visual elements. * **Increased Output Potential:** Companies like Luma AI aim to drastically increase film production volume, with CEO Amit Jain suggesting a shift from making five movies a year to potentially 50 or 100, acknowledging that many might be "slop" but increasing the odds of hitting a success. * **The "Ouroboros" Effect:** A concern is raised that as AI models are trained on existing data, they may eventually have nothing new to draw from, leading to a recursive and less interesting form of cinema. ### Notable Risks and Concerns: * **Job Displacement:** The automation of tasks currently performed by artists, illustrators, and other below-the-line specialists is a significant concern, with illustrators like Reid Southen reporting a substantial decrease in income due to AI replacing human work. * **Erosion of Artistic Integrity:** Critics fear that the ease of AI generation will lead to a proliferation of derivative, soulless content that lacks the depth and emotional resonance of human-created art. * **Copyright Infringement and Exploitation:** The use of copyrighted material to train AI models without proper licensing or compensation raises serious ethical and legal questions. * **Devaluation of Human Creativity:** The argument is made that AI-generated content, even if technically proficient, may lack the "human touch" and the unique problem-solving that arises from human collaboration and struggle. * **Unintended Consequences:** The rapid adoption of AI in filmmaking could lead to unforeseen societal and cultural impacts, altering the landscape of creative industries. ### Material Financial Data: * **Cost Savings Potential:** James Cameron suggests that AI could "cut the cost of that [effects-heavy films] in half," a key driver for studio adoption. * **Production Budgets:** The Russo brothers' Netflix film *The Electric State*, which reportedly utilized AI for some effects, cost over $300 million to produce, indicating that AI integration does not yet guarantee cost reductions on large-scale projects. ### Key Figures and Companies: * **Natasha Lyonne & Bryn Mooser:** Co-founders of Asteria, an AI entertainment startup. * **C. Craig Patterson:** Indie artist and director, collaborating with Asteria. * **Moonvalley:** CAA-backed firm developing "ethical AI-tools." * **Brit Marling & Jaron Lanier:** Collaborating on Asteria's AI film *Uncanny Valley*. * **Runway AI:** A prominent AI company with deals with Harmony Korine's EDGLRD, Pablo Larraín's Fabula, and AMC Networks. * **Luma AI:** Startup behind Dream Machine and Modify, opening a lab in Hollywood. * **Justine Bateman:** Actor and filmmaker, a vocal critic of AI in filmmaking. * **Reid Southen:** Film concept artist and illustrator, advocating against AI's impact on labor. * **James Cameron & Timur Bekmambetov:** Directors embracing AI in their work. * **Darren Aronofsky:** Partnered with Google DeepMind, exploring AI for storytelling. * **Peter Docter:** Chief Creative Officer at Pixar, questioning the extent of AI's role. * **Midjourney:** Image-generation company facing copyright infringement lawsuits from Disney and Universal. * **Wonder Dynamics:** AI work-app company whose division is involved in AI-enhanced visual effects. * **OpenAI:** Company behind Sora, its video tool being used in various film projects. * **Teamsters President Sean O’Brien:** Leading opposition voices advocating for AI protections. * **John Lopez:** Veteran screenwriter, emphasizing the value of human collaboration. ### Recommendations (Implicit): While not explicitly stated as recommendations, the report highlights the need for: * **Legal Clarity:** The outcome of lawsuits like Disney and Universal v. Midjourney will be crucial in defining the legal framework for AI in creative industries. * **Labor Protections:** The WGA contract and ongoing discussions with unions like SAG and Teamsters indicate a need for robust protections for human workers. * **Ethical Guidelines:** The development and adoption of AI in filmmaking should be guided by ethical considerations regarding originality, attribution, and fair compensation. * **Artistic Intent:** Filmmakers and studios must carefully consider how AI is used to enhance, rather than replace, human creativity and emotional storytelling. The report concludes that Hollywood is at a critical juncture, facing an "AI civil war" that will fundamentally reshape the industry, with the outcome of this conflict determining whether AI becomes a tool for unprecedented creative expansion or a force that erodes the very foundations of human artistry and labor.

Rise of the Machines: Inside Hollywood’s AI Civil War

Read original at The Hollywood Reporter →On a chilly day at a vintage studio building on the Eastside of Los Angeles, Natasha Lyonne sat in front of a large-screen TV and played with a joystick.The device in her hand looked a lot like a vintage Atari 2600 paddle, and as she spun it one way, then the other, images appeared, shapeshifted and melted into various forms of digital surreality; at one point the model generated a tableau it called “Artpixel Monochromatic Media Shower Fractal 3.

”Lyonne would occasionally emote to the two men sitting near her, who sometimes took the paddle. “Go back to the Rothko,” she exclaimed in her unmistakable Long Island rasp at one point, as onscreen an image popped up in the style of the American abstract expressionist and then just as quickly disappeared.

Lyonne is the co-founder of Asteria, an AI entertainment startup of the kind that has begun to dot both coasts like a news map in an alien-invasion movie. She was seated in the company’s headquarters, in a historic building at one time run by the troubled Charlie Chaplin collaborator Mabel Normand — two complicated, successful Hollywood women, a century apart.

Lyonne’s mission in the joystick session was, in her technical coinage, “just to fuck around.” A staffer had created the device to test the idea that images could be generated with not text prompts but tactile scrolling. The effort was telling. This was an attempt to see what filmmaking looked like when the creative brain starts to merge with the machine mind.

“It feels here what the beginning of Pixar must have felt like,” Lyonne said. “Everyone is in the Imagineering phase — very blue-sky, very inspiring, all trying to crack the code.”Next to Lyonne, one of the two men by her side — her Asteria co-founder and romantic partner Bryn Mooser — nodded. “But hopefully we’ve already cracked a few of them,” he said.

The second man, the indie artist and director C. Craig Patterson, gave a coy smile.On this day, Lyonne and Mooser had yet to announce (but were already developing) Uncanny Valley, the AI film that Asteria and its parent company, the CAA-backed “ethical AI-tools” firm Moonvalley, are making with Brit Marling and the virtual reality pioneer Jaron Lanier.

The project marks one of the first major efforts to build a whole film around machine-generated media. But the hoopla of such announcements obscures all the ways AI is already lodged inside our filmmaking.Hollywood is currently in the midst of an AI insurgency, though even that noun may not do the moment justice.

Though still fragmented, the effort is increasingly looking like a full-on takeover, a Pixar-like artquake that aims to change the provenance of images, the business of production and (not to put too fine a point on it) the language of cinema itself.The movement is building from several directions — from Hollywood-adjacent startups like Asteria and Runway AI; from AI-curious traditional entertainers like the directors James Cameron and Timur Bekmambetov and Lyonne and Darren Aronofsky (who’s partnered with Google DeepMind); from studio executives aflutter with the thought of massive cost savings; from an assortment of effects and other below-the-line specialists attracted to (if slightly wary of) the whizbangery; and, of course, from executives at companies like Google and OpenAI, who gaze upon the possibility of an automated Hollywood with the same disbelieving glee of an insulin dealer who has just stumbled upon a diabetic convention.

Veo 3 and Gen-4, Sora and Luma — the names of the generative video products at the center of the movement carry an abstract, almost ersatz quality. What can these things do, we wonder, and what will they make us do? But if their branding feels opaque, their goal couldn’t be clearer: for a machine to create, with just the slightest nudging from us, the kind of cinema that for more than a century only could exist when a group of people got together in a physical space to construct and record it.

In the past few months alone, Runway AI has announced deals with Harmony Korine’s EDGLRD, Pablo Larraín’s Fabula and AMC Networks to go along with the dozens of studios and production companies informally playing with the company’s tools to figure out their value and limits — a backdoor introduction of machines into the house of storytelling.

In response to this ambition, a countermovement has arisen, a prickly resistance to the idea of removing creativity from human hands. It has coalesced around high-profile spokespeople like the actor-filmmaker Justine Bateman and designer Reid Southen, who worry about the effect on artistry and humanity.

Their resistance has been bolstered by SAG and WGA and other labor groups panicked about the effect on available jobs. And, sometimes paradoxically, even by the studio bosses themselves, who wonder, notwithstanding all those tantalizing bags of money saved, if allowing a computer system to swallow up the millions of hours of moving images they created so it can take over the creation itself is the best idea — whether that will yield the next Pixar or, as seems equally plausible, just the demise of the old one.

“We get together in the Atrium all the time and talk about this,” says Peter Docter, chief creative officer at the current Pixar. “How much should we be letting the machines do the work?”***Cinema is built on illusion. The Lumière brothers famously (if perhaps apocryphally) scared 1896-era audiences of Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat into believing that a train was actually barreling into the theater.

Some 80 years later, the early Imax film To Fly seemed so real with its airborne panoramas that many filmgoers experienced vertigo. As recently as 2010, numerous audience members fainted watching James Franco slice his arm off in the climactic act of self-preservation in Danny Boyle’s 127 Hours.Filmmakers clearly constructed all these scenes, a fact that neither trips our ethical wires nor stops our biological reactions.

If anything, the ability of filmmaking technology to trick us into believing something is really happening makes the work more worthy of our approval. The grander the illusion, the higher the praise.AI tests that theory in a reductio ad absurdum way. It is, in one sense, the ideal illusion, tech creating the next jaw-dropper to induce running or fainting without the requirement of any real-world duct tape to make it happen; you simply snap your fingers and it appears.

But AI also destroys the organic roots of that illusion. The compact of cinema for its roughly 125 years of existence is that we accept all the trickery onscreen because we know it was created by humans standing behind it — that whether the Death Star is being blown up or Chow Yun-fat and Michelle Yeoh are flying through the air in a sword fight, those born of flesh-bound mother and in possession of human brain came together, puzzled over a problem and figured out its solution to give us the art that we now see.

Whatever didn’t happen involved a lot of people to make happen. An AI scene, on the other hand, happened because someone uttered some magic words and little pieces of silicone ran through 80 trillion calculations per second.“Humans always figured it out,” says Bateman, who has emerged as one of Hollywood’s most vocal anti-AI activists.

“That great shot at the beginning of Sunset Boulevard where you’re looking up from the bottom of the pool past the body to the photographers. That’s such an imaginative shot. They used a mirror to get it. If they had AI, they wouldn’t have resorted to that. And we would have been robbed of one of the great shots in cinema.

”A scene from the Runway AI movie “Total Pixel Space.” AI is already inside Hollywood — and used to make Norman Rockwell images as much as interplanetary ones.Runway AIBateman says relying on AI is exploitative because it in fact can only make its calculations based on all that humans did before. That presents an obvious labor-ethics challenge, since none of those humans seems likely to be paid or credited.

But even more problematically, she says, it makes for an existential problem, since it means human artistic effort as we’ve known it pretty much since the hieroglyphs is now stopped in its tracks. “Using AI for a shot,” she says, “is a regurgitation of the past.” Suffice to say that is not how the insurgents see it.

As Patterson at the Normand studio tinkers on a screen for a short he is making for Asteria, Mooser looks on approvingly. The filmmakers poring over AI see in this fresh tech a kind of efficiency transformation that gives the whole enterprise new utility, the way the cellphone didn’t just improve what Alexander Graham Bell had devised but changed the nature of communication itself.

“We can do things faster and cooler than ever,” Patterson says. “And the best part is we don’t even know yet what it can do.”Last week, Luma AI, the startup behind a set of slick video tools called Dream Machine and Modify, announced a new lab in Hollywood. The company’s aim, CEO Amit Jain tells me, is to crank up output in ways current economics would never allow.

“Why are you making five movies a year when you should be making 50, you should be making 100?” he says. Jain acknowledges that many of these could be slop. But he offers a punchy bit of logic: You have a much greater chance of putting one over the left-field wall with 95 more at-bats.Asteria, meanwhile, has already dropped AI into its films.

Not long before the fuck-around session, the company debuted the documentary Free Leonard Peltier at Sundance. Centering on the jailed Native American activist — it premiered just days after President Biden granted him clemency — the film looks to tell Peltier’s story from the inside.As participants and experts recall what happened that day, we watch from Peltier’s perspective as he tries to flee the reservation and elude FBI capture.

These reenactments by now feel familiar; documentarians from Errol Morris on down have been doing them for decades in the absence of archival footage. Only it’s not a reenactment. Our seasoned documentary eyes don’t stop to consider a third possibility — that capturing this singular moment of Peltier running didn’t involve going to a spot in the Dakotas, standing in a specific time and place, and imagining what he must have been feeling.

Instead, a computer was told to do the imagining for us.To those practicing the form, that is a virtue. Even the most adroit filmmaker in the age of iPhones will say that some scenes are just too hard to capture, that cinema is constrained by reality. AI-generated film promises to collapse all that — to shrink to zero the barrier between wanting a shot and making it happen.

Indeed, to watch these tools in action — a whole cityscape springing out of the earth, people dancing across a field in intricate choreography — is to find one’s mind if not blown, then at least experiencing a very hot wind. Text-to-video tools elicit God-like vibes, and also slightly cheaty vibes, like the first time you logged into ChatGPT and had it write a thank-you note from nothing — except now multiplied to the power of Spielberg.

Something that would have taken dozens of people and hours to produce just appeared in front of me, and I got away with it.“What this tech enables you to do is take anything inside your brains and bring it to life immediately,” Alon Soran, chief commercial officer at EDGLRD, told me when the Runway deal was announced.

EDGLRD has used AI in a number of its productions, including a hybrid-media film called Baby Invasion that premiered at last year’s Venice Film Festival and a campaign for Valentino’s recent fall-winter collection. “For the first time, our ability to make things is at the same pace as our ability to think of them.

”That is a powerful idea. And one with the potential for a lot of unintended consequences.***In June, Disney and Universal filed a copyright-infringement lawsuit against the image-generation company Midjourney. Alleging a “bottomless pit of plagiarism,” the companies are seeking to stop the startup — and its much larger and better-funded competitors — from grabbing all the movies they’ve made to feed into its model.

“If a Midjourney subscriber submits a simple text prompt requesting an image of the character Darth Vader in a particular setting or doing a particular action, Midjourney obliges by generating and displaying a high quality, downloadable image featuring Disney’s copyrighted Darth Vader character,” the complaint says.

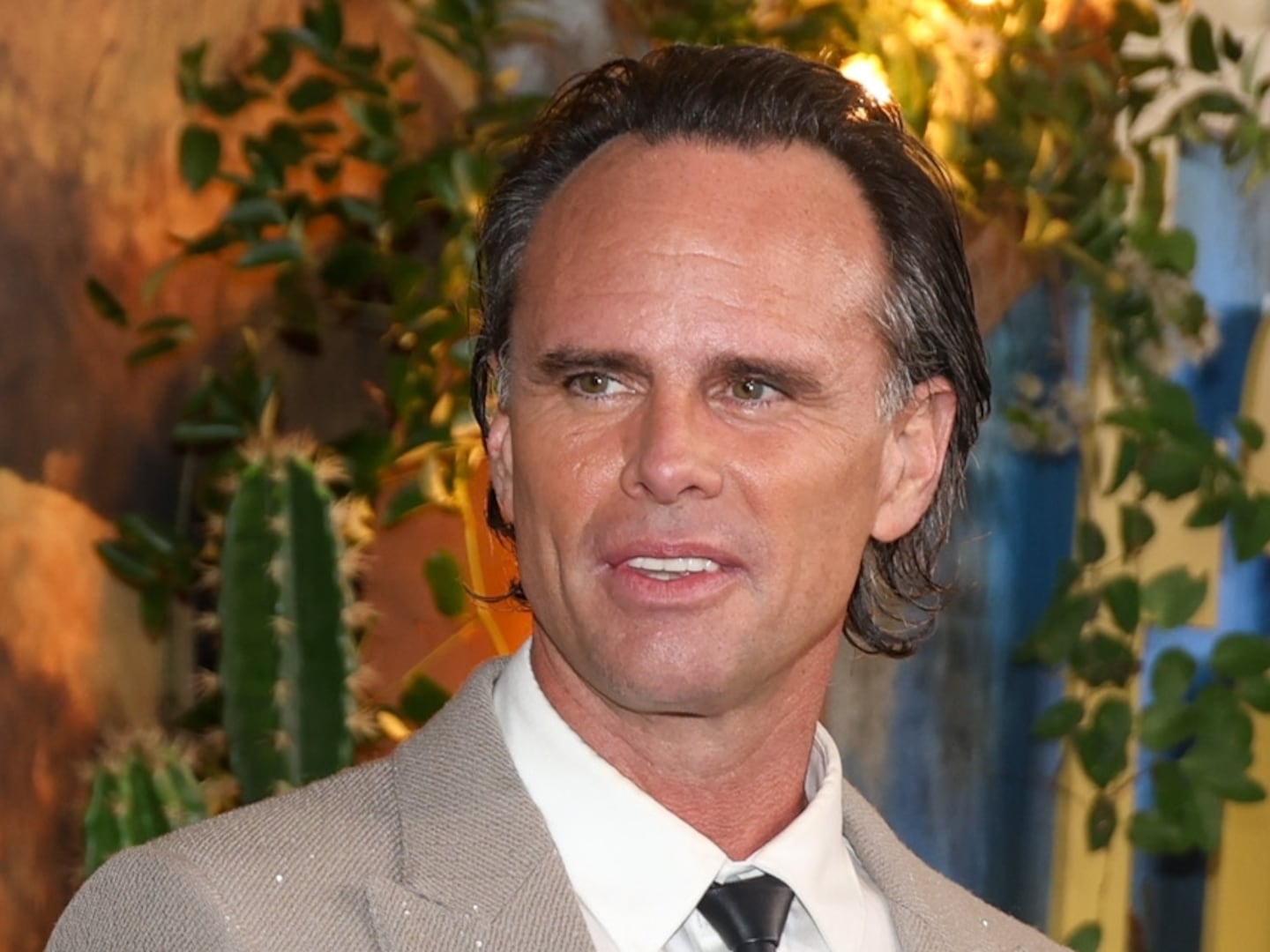

Studio executives sit on a strange fault line of the AI insurgency, thrilled by the production money they can save in an ever-chillier climate for their product, yet terrified that consumers might look to save their own money and just make the product themselves.Asteria founders Bryn Mooser and Natasha Lyonne at the 2024 Gotham Awards at Cipriani Wall Street.

The pair are part of the movement to bring AI to Hollywood.(Photo by James Devaney/GC Images)The budget benefits are certainly real. Those in the AI insurgency like to point out that indie filmmakers will now operate on a studio level while garden-variety studio filmmakers can act like James Cameron.

And Cameron himself? He’d be free from having to convince a studio to spend $300 million on his latest vision — perhaps one reason he’s gone from comparing AI to a nuclear arms race to extolling the tech. “If we want to continue to see the kinds of movies that I’ve always loved … big effects-heavy, CG-heavy films, we’ve got to figure out how to cut the cost of that in half,” he said on a Meta podcast recently.

“That’s my sort of vision for AI.”But for all the cash AI could save them, it remains far from clear whether members of the studio establishment realize that the chance to automate content will at the very least drastically change their business model (why go through the risky bother of generating new material when you can just let people play with what you already have?

) and at most eliminate the need for large-scale production and distribution altogether.The studios are reacting the way studios react when a whole bunch of their stuff ends up in places they didn’t authorize: They’re suing.Judges have recently ruled for Silicon Valley companies against two groups of authors, in copyright-infringement cases filed in tech-friendly San Francisco.

But Disney and Universal’s suit against Midjourney, crucially, was filed in Los Angeles, where courts are more likely to be sympathetic to Hollywood. How the judge sees the case could well determine the future of a traditional professional production model in the AI age.Paul Thomas Anderson and Wes Anderson will always be Paul Thomas Anderson and Wes Anderson, of course, and it’s highly unlikely their brand of bespoke film will change.

But the AI age might not produce much of a new Andersonian generation if there is no studio ecosystem (or commercial market) to support that type of human-guided film. Given its lower costs, automated media doesn’t need to match human-led work — it need only be good enough. Offering a hint of that new math this summer is the AI “provocation” The Velvet Sundown and the band’s Spotify hit “Dust on the Wind.

” With its respectably generic sounds and million monthly listeners, the song offers a glimpse of a coming world of creativity where the risk-reward for human-centric work rarely adds up.And while Aronofsky’s AI company Primordial Soup will no doubt deploy LLMs to interesting effect (the company’s unofficial motto is “make soup not slop”), most of the people churning out AI movies won’t be Darren Aronofsky.

Just because Bon Iver uses auto-tuning doesn’t mean its net artistic effect is positive.Instead, what the AI insurgency could yield is a different kind of creation. There’s a radical thought that AI cinema will help the film world conjure not just scenes but people — “digital humans” that will look and move like real actors without any of the pesky concerns of a bad day, or residuals.

If that were to happen, our films would change in unthinkable ways. Humphrey Bogart could be acting opposite Selena Gomez. New actors we’ve never heard of because they’re not people at all could win Academy Awards.But we don’t need to spin such a fanciful scenario to see how AI will change the grammar of film.

An evolution already came this spring with The Electric State, a Russo brothers Netflix movie with Chris Pratt and Millie Bobby Brown, filled with all manner of robots and nonhuman creatures.While the film hardly set critics afire, with its FX-driven wild futuristic beings and robots engaging in wild futuristic expressions, it hinted at what the language of cinema might look like in an AI age.

Indeed, some of the robot effects were handled by Wonder Dynamics, a West Hollywood-based division of an AI work-app company called Autodesk.One of Wonder Dynamics’ innovations is that, rather than taking stock creations and dropping them in — a kind of AI 1.0 — it allows a level of in-scene manipulation.

“Our big belief is that whatever we build needs to be editable and controllable,” the company’s co-founder, special-effects guru Nikola Todorovic, tells me.If such innovations catch on, we might ultimately have entire new genres made possible by AI. Rather than digital humans taking the place of actors in our existing genres, cinema could be dominated by stories that lend themselves to these cheaper, manipulable and non-Guild-eligible AI creatures.

(Such creations would cleverly circumvent SAG guardrails; what does it matter if an actor needs to give their consent if you’re not using actors in the first place?)The ability to so easily joystick characters’ movements and even emotions within a scene will, simply put, result in us seeing a lot more of them.

For all its loud incoherence, The Electric State could eventually be viewed less as a head-scratching, made-for-streaming afterthought than the proto version of a new way of thinking about film that simply had yet to work out the kinks, the way the original Tron offered a portentous glimpse into what Hollywood’s effects age would eventually look like.

As for AI saving money? Not yet. The Electric State reportedly cost more than $300 million to produce.***One recent afternoon in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood, Runway AI co-founder Cristóbal Valenzuela sat in his company’s conference room and talked about a flying Coke can.The day before, a notable director had sat at the same table and been wowed, according to Valenzuela, by an AI model that with nothing more than a prompt had made the beverage up and fly off the table in an onscreen reenactment.

It’s the kind of filmic trick current LLMs barely break a sweat pulling off but that can nonetheless dazzle people who’ve spent their lives shouldering the difficulty of making objects do things objects don’t normally do.“When artists come in and see what’s possible, they’re instantly excited,” Valenzuela says.

“And we’re instantly excited to see how we can help them.” The story has a dual purpose. First, it suggests that Runway AI is, as its executives like to say, just a “tool” to assist great artists, no different or more soul-stealing than providing Picasso with a fresh set of paintbrushes. And second, it suggests that really big directors are showing up to hear about it.

While nearly all of what Runway does takes place inside a computer, Valenzuela and his partners had taken pains to decorate their office with the warm touches of analogue creativity. A vintage Polaroid camera sat on one shelf, a set of books about tapping into one’s inner muse lay on another. In one corner, a set had even been built for an animated sci-fi detective story the company was producing.

“We didn’t need to, but it just helped inspire us,” Valenzuela says. The scene was something of a mind scramble. For years, filmmakers have tinkered with designs on a computer to prepare to make a movie on a physical set. Now, the equation had been reversed.In another corner of the office, an engineer who used to work at Marvel was tweaking a model to allow for the seamless creation of a car chase, the kind of scene that involves a careful set of continuities that can tax a piece of computer code that has never set foot in a car.

What the engineer was doing, like so much of what Hollywood AI companies are doing, wouldn’t be dropped specifically into a film. But he was refining a model so that someone, somewhere, could at some point. In Runway’s vision, when the next William Friedkin wants to thrill us, he won’t need Popeye Doyle to commandeer a LeMans and narrowly avoid hitting a baby carriage — he just has to use a machine that knows a movie that once did.

A Chilean with an easygoing thoughtful manner, Valenzuela founded Runway with two fellow millennials, Alejandro Matamala Ortiz and Anastasis Germanidis, after the three met at the cutting-edge ITP program of NYU, which crossbreeds technology and art. Among the trio, Valenzuela is the avowed cinephile, the one who has been both reassuring Hollywood and pushing his staff to contour products for it.

(Runway’s tools “Act-Two,” “Gen-4” and “Gen-4 References” are, unlike OpenAI’s, specifically designed to solve challenges in filmmaking, like allowing characters to look the same from scene to scene, a major problem for a memory-deficient machine.) Among the company’s deals is a high-profile pact with Lionsgate, and it has loaned its tools out to nearly every major studio to play around with, sometimes even placing an employee on the lot as a consultant to guide them.

Several weeks after the meeting, the company would rent out Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall for an “AI Film Festival.” Valenzuela stood in front of a cheering crowd and noted how “millions of people are making billions of videos using tools we only dreamed of,” after which 10 decidedly dreamy, almost experimental films (character dialogue is still hard in AI movies) were screened for the audience.

While undeniably possessed of vision, none of the films acknowledged all the previous artists’ work they had drawn from nor, more important, the future work they can cut into.I asked Valenzuela why he didn’t feel all these models were impinging on what makes movies human. “They said the same about Industrial Light & Magic — ‘It’s too much technology, it’s not art,’” he said, then added with a friendly but pointed edge, “Imagine if we’d listened.

”Someone who is certainly not listening is Bekmambetov, the Kazakh genre auteur of Wanted and Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter. Bekmambetov has been shepherding a series of films that he dubs screenlife, which aims to capture our digital moment by filming entirely within screens, and as part of that he’s pushing into an AI future, both thematically and technically.

A new film he’s in production on now, a biopic called Luria, will be generated largely by AI. SAG may want to call off the wolves, though: Bekmambetov is jujitsuing AI’s tendencies against it, having the models generate false visions as part of the protagonist’s research into neuroplasticity, the science of shifting brain morphologies.

“It’s a trick,” Bekmambetov says. “I started this project seven years ago but couldn’t make it — too expensive. It’s 90 minutes of visual effects showing hallucinations. Now all the existing AI models create hallucinations.”Wonder Dynamics’ tools allow for human characters to be replaced in footage by AI-enhanced ones, such as this crash test dummy.

The director believes any filmmaker not using AI in an unusual way will find themselves disappointed; the tech thinks too pragmatically for art.“People will still flip tables in the temple,” says Bekmambetov, whose upcoming Amazon/MGM sci-fi film Mercy has a very human Chris Pratt wrestling with a very AI-seeming Rebecca Ferguson.

“The machine tries to simplify looking for a result … a solution straight ahead. But humans wonder what’s behind the corner.” That distinction, he says, is the difference between art and infomercials, and is why AI will struggle with the former.Such a phenomenon may be on display with some OpenAI attempts at cinema.

The Sam Altman-run company has had a herky-jerky relationship with filmmakers, seemingly cognizant that, unlike Runway, it is not really a creative-minded entity and its platforms are a lot more likely to be used by developers building an AI assistant than a product that helps you cosplay Scorsese.

Plus, some filmmakers are straight-up wary of working with a company they see as coming to automate their jobs. (We’ll also see how Hollywood feels about Altman when Amazon releases its OpenAI drama Artificial, which looks to begin shooting this summer with Luca Guadagnino directing and Andrew Garfield as the provocative mogul.

)Yet OpenAI reps have hung around film festivals and made entrées to filmmakers and studios, while Sora, the company’s video tool, has been used for a host of films from interesting artists. One of them is Air Head, a micro-short from the Toronto pop collective shy kids.Air Head tells a story of a man with a balloon for a head who keeps a positive attitude as he goes (well, floats) through life.

The voiceover piece leans into the dreamlike power of Sora, first by the mere fact of its whimsical story and then, as the head floats around the world, building in all the big global set pieces that a text-to-video tool so easily can whip up.But Air Head also inadvertently shows the problems with letting machines take creative lead on your film, with the movie exuding a soullessness that feels apt for images originating outside a human brain.

“The dystopia is coming, but boy are the neon lights pretty,” one commenter posted on YouTube.“Wow this is like a totally sick ad for a mid-tier credit union,” another wrote.***Automating cinema that used to be human-made risks change on two fronts: You take the human out of the process, and you take the humanity out of the result.

The first score brings a host of labor challenges. Job displacement as not a far-off fear but an imminent peril is articulated from within Hollywood most persuasively by Reid Southen. A film concept artist and illustrator who has worked on franchises from The Matrix to The Hunger Games, Southen has been instrumental in getting Hollywood rank and file to see the power of the tech to automate away human jobs.

He says that his income has been slashed roughly in half in the past two years, not because studios are turning to other illustrators but because they’re turning to no illustrators at all, relying on AI programs like Stable Diffusion, Midjourney and OpenAI’s DALL-E to do it for them.Video remains glitchy and new, but still images are something AI has been doing for a few years now, and Southen has fervently made the case that what has happened to him is about to happen to a lot more people.

“If they can pillage and plunder everyone’s work to replace you, it will destroy whole creative industries,” he told me in May. “They may make money in the short term,” he adds of studios, “but in the long term it will destroy them.”Even the flawed nature of the models — a common refrain among those who say machines can “never replace” humans doing creative work — won’t help, he says.

“They’ll throw a bunch of stuff at the wall and bring an artist in only when they absolutely have to,” he says.(AI, it should be noted, has yet to infiltrate script development because the post-strike WGA contract disallows studios from doing exactly what Southen describes. What the next contract, due in less than 10 months, will bring is less clear.

Writers themselves, an informal survey indicates, are not really using AI as a shortcut, save for occasional compressions. The blame for that shaky script can stay on the humans.)Hollywood illustrator Reid Southen put together a side-by-side comparison of images from Jurassic Park and the video-generation tool Midjourney Those toiling in the space see AI as a boon for human labor.

“When greenscreen came into the industry, it took 1,500 jobs but created hundreds of thousands more because now you had all these large-scale movies that could never have been made before,” Patterson, the Asteria director, tells me. “I look at generative AI the same way. It’s an opportunity for artists to come and build.

”But the analogy ignores a key difference between greenscreens and LLMs. The former inflated productions to tentpole size; the latter will likely move a lot of productions from the set to the control room. Why hire a huge, expensive crew to shoot on location for weeks when five people huddled over a laptop can prompt their way to the same scenes?

Such realities have not gone unnoticed by the pushback crowd. “I mean, you can make a movie on an iPad and create Hollywood characters,” says Sean O’Brien, the Teamsters president who has emerged as one of the leading opposition voices. Rather than leaning into AI artistically, he says, the industry needs to marshal its neutralization efforts.

All those who care about human labor must “be vigilant on making sure there are protections against AI, utilize AI where it’s necessary and where it’s not necessary mandate that it can’t be used,” he tells THR.But for all the land mines on the labor issue, the second question, of what AI will do to the result, might even loom larger.

Licensing fees, should they come in those agreements, will solve legal challenges, and at least restore some equity and compensation to what is, at the moment, a wild West of exploitation. But it will not solve, and indeed in many ways could worsen, the more artistic problem of what it means for so much of our art to be a Batemanian regurgitation of the past.

Saying that people will get paid for the reboot doesn’t make for any less of a reboot. And traditional reboots at least involve artists trying to bring their own spin. What AI threatens to do is put reboot culture on steroids by taking it out of the hands of creators entirely.“Even the biggest studio moneygrabs are the product of 500 humans, desperate artists competing with each other and banging their head to make something good,” says the veteran screenwriter John Lopez.

“AI preempts that process because it reduces everything to one person working with a model. And there’s no way one dude at a keyboard has the creative impulses to put something on the screen that matches the information in 500 brains.”Lilo & Stitch may exemplify modern Hollywood’s tendency to cynically repackage what worked in the past so it can be resold to the same audience two decades later.

But the new film is a genuine artistic creation, with an Oscar-nominated director, a veteran producer and a diverse cast. Cinema’s AI age could return a whole different kind of Lilo & Stitch, with none of those bona fides, just a thousand sloppified versions of a girl and her alien dog bonding over ohana in the United States of Personalized Content.

From left: Runway AI’s Alejandro Matamala-Ortiz, Anastasis Germanidis and Cristóbal Valenzuela, photographed outside their Manhattan offices in 2023.Should such a world happen, it could lead to a Hollywood that looks a lot more like social media. And if you’re the kind of person who finds genius in memes, there will be something to admire in these new reappropriated forms.

The de-professionalization may even be encouraging on a populist level, putting cinema in the palms of the many. But art is also inherently elitist. And it seems reasonable to ask if, in eroding this elitism, aspects of art get junked too.At the Tribeca Film Festival a few weeks ago, Aronofsky premiered Ancestra, Eliza McNitt’s 45-minute film produced by Primordial Soup.

At the event, Aronofsky laid out a vision that will be heartening to anyone hoping that the AI age can retain the human.“The slop is just mind-blowing in the sense that you’re like, ‘Whoa, I’ve never seen that before,’” said the director. “But none of it stays with you. It gets your attention for a second and it really works well on the socials … but it doesn’t really stay with you and that’s because there are no stories, there are no emotions to it.

”Aronofsky said his mission was to locate them in the machine. “There are lot of ways to use these models. I’m mostly interested in figuring out how to use these models to tell stories.”But he admitted he was still early in that process, and even his polished hands had yet to figure out how to coax narratives from the code, or if they were even coaxable.

If they are, it raises one final set of questions: Where does the newness eventually come from? Because if the models synthesize everything human that ever was, what happens when so many meaningful combinations are exhausted? What happens when the AI has nothing left to draw from but itself? At that point, could we be headed for a kind of cinema of the ouroboros, an endlessly recursive set of outputs that gets less and less interesting as it becomes more and more inbred?

Art has always drawn from the past but also pushed inexorably into the future. An AI that by definition looks backward makes you wonder if there is anywhere left to go.