## Summary of "Today’s humanoid robots look remarkable, but there’s a design flaw holding them back" **News Title:** Today’s humanoid robots look remarkable, but there’s a design flaw holding them back **Report Provider:** The Conversation **Author:** Hamed Rajabi **Published Date:** August 8, 2025 This article from The Conversation, authored by Hamed Rajabi, argues that despite impressive advancements in humanoid robots like Boston Dynamics' Atlas and Tesla's Optimus, a fundamental design flaw is hindering their widespread adoption and true potential. The core issue lies in a **"brain-first" approach** that prioritizes centralized AI control over the physical design of the robot's body. ### Key Findings and Conclusions: * **Limited Physical Intelligence:** Current humanoid robots have a **"limited number of joints"** and are often rigid assemblies of metal and motors. This creates a **"disparity between their movements and those of the subjects they imitate,"** significantly diminishing their value. * **Energy Inefficiency:** The "brain-first" design forces robots to make millions of constant, power-hungry corrections to maintain balance. This leads to significant energy consumption. * **Example:** Tesla's Optimus robot consumes approximately **500 watts of power per second** for a simple walk, while a human uses only around **310 watts per second** for a brisk walk. This means the robot uses **nearly 45% more energy** for a less demanding task, highlighting a considerable inefficiency. * **Diminishing Returns from AI:** While AI progress is rapid, it leads to diminishing returns when the underlying physical hardware is not optimized. Even a smart robot like Optimus, capable of folding a t-shirt, struggles with unpredictable environments due to its rigid, sensor-poor hands. It relies heavily on vision and AI to compensate for its physical limitations. * **Physical Weaknesses of Advanced Robots:** Even Boston Dynamics' new all-electric Atlas, despite its impressive range of motion, cannot navigate challenging real-world terrains like mossy rocks or dense vegetation because its feet cannot conform to surfaces and its body cannot yield and spring back. This is why these robots remain primarily **research platforms** rather than commercial products. * **Root Cause: Industry Focus and Supply Chain:** Leading robotics firms are primarily software and AI companies, with supply chains optimized for high-precision motors, sensors, and processors. Building physically intelligent robot bodies requires a different manufacturing ecosystem rooted in **advanced materials and biomechanics**, which is not yet mature enough for large-scale production. * **The Promise of Mechanical Intelligence (MI):** The article advocates for a shift towards **mechanical intelligence (MI)**, a field focused on designing a machine's physical structure to achieve **passive automatic adaptation** without requiring active sensors, processors, or extra energy. This approach draws inspiration from nature's "morphological computation," where bodies perform complex calculations automatically through their physical design. * **Examples of MI in Nature:** * A pine cone's scales opening and closing based on humidity. * The tendons in a hare's leg acting as intelligent springs to absorb shock and store energy for efficient gait. * The human hand's soft flesh conforming to objects and fingertips acting as smart lubricators for optimal friction. ### Recommendations: * **Embrace Mechanical Intelligence (MI):** The industry needs to move beyond the "brain-first" approach and focus on developing **"smarter physical bodies"** that possess inherent physical intelligence. * **Redesign Robot Bodies:** This involves incorporating principles of biomechanics and advanced materials to create **"flexible structural mechanisms"** that allow for dynamic and efficient motion. * **Develop Hybrid Components:** Research into components like **"hybrid hinges"** that combine the precision of rigid joints with the adaptive properties of compliant ones is crucial for creating more human-like movement. * **Synthesize Hardware and Software:** The future of robotics lies not in a competition between hardware and software, but in their **synthesis**. By embracing MI, robots can become more capable and finally transition from research labs into the real world. ### Notable Risks and Concerns: * The current "brain-first" approach leads to **diminishing returns** and creates a cycle where advanced AI requires increasingly powerful and energy-hungry hardware. * Robots designed with the current philosophy are **physically fragile and inefficient**, limiting their practical applications in unpredictable real-world environments. * The lack of a mature manufacturing ecosystem for physically intelligent robot bodies is a significant barrier to widespread adoption. In essence, the article argues that while current humanoid robots are visually impressive, their fundamental design flaw—a lack of inherent physical intelligence—is preventing them from achieving their full potential and requires a paradigm shift towards mechanical intelligence.

Today’s humanoid robots look remarkable, but there’s a design flaw holding them back

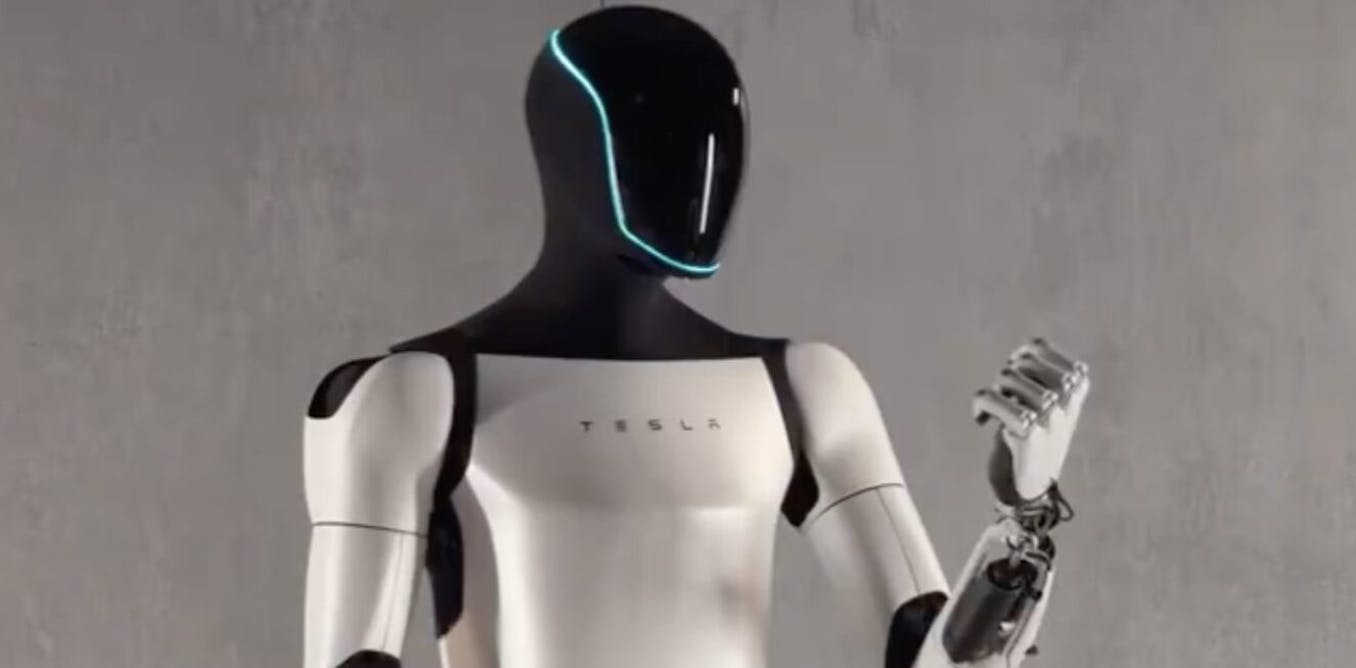

Read original at The Conversation →Watch Boston Dynamics’ Atlas robot doing training routines, or the latest humanoids from Figure loading a washing machine, and it’s easy to believe the robot revolution is here. From the outside, it seems the only remaining challenge is perfecting the AI (artificial intelligence) software to enable these machines to handle real-life environments.

But the industry’s biggest players know there is a deeper problem. In a recent call for research partnerships, Sony’s robotics division highlighted a core issue holding back its own machines. It noted that today’s humanoid and animal-mimicking robots have a “limited number of joints”, which creates a “disparity between their movements and those of the subjects they imitate, significantly diminishing their … value”.

Sony is calling for new “flexible structural mechanisms” – in essence, smarter physical bodies – to create the dynamic motion that is currently missing. The core issue is that humanoid robots tend to be designed around software that controls everything centrally. This “brain-first” approach results in physically unnatural machines.

An athlete moves with grace and efficiency because their body is a symphony of compliant joints, flexible spines and spring-like tendons. A humanoid robot, by contrast, is a rigid assembly of metal and motors, connected by joints with limited degrees of freedom.To fight their body’s weight and inertia, robots have to make millions of tiny, power-hungry corrections every second just to avoid toppling over.

As a result, even the most advanced humanoids can only work for a few hours before their batteries are exhausted. To put this in perspective, Tesla’s Optimus robot consumes around 500 watts of power per second for a simple walk. A human accomplishes a more demanding brisk walk using only around 310 watts per second.

The robot is therefore burning nearly 45% more energy to accomplish a simpler task, which is a considerable inefficiency.Diminishing returnsSo, does this mean the entire industry is on the wrong path? When it comes to their core approach, yes. Unnatural bodies demand a supercomputer brain and an army of powerful actuators, which in turn make robots heavier and thirstier for energy, deepening the very problem they aim to solve.

The progress in AI might be breathtaking, but it leads to diminishing returns.Tesla’s Optimus, for instance, is smart enough to fold a t-shirt. Yet the demonstration actually reveals its physical weakness. A human can fold a t-shirt without really looking, using their sense of touch to feel the fabric and guide their movements.

Optimus, with its relatively rigid, sensor-poor hands, relies on its powerful vision and AI brain to meticulously plan every tiny motion. It would likely be defeated by a crumpled shirt on a messy bed, because its body lacks the physical intelligence to adapt to the unpredictable state of the real world.

Boston Dynamics’ new, all-electric Atlas is even more impressive, with a range of motion that seems almost alien. But what the viral acrobatics videos don’t show is what it can’t do. It could not walk confidently across a mossy rock, for instance, because its feet cannot feel the surface to conform to it.

It could not push its way through a dense thicket of branches, because its body cannot yield and then spring back. This is why, despite years of development, these robots mostly remain research platforms, not commercial products.Why aren’t the industry’s leaders already pursuing this different philosophy?

One likely reason is that today’s top robotics firms are fundamentally software and AI companies, whose expertise lies in solving problems with computation. Their global supply chain is optimised to support this with high-precision motors, sensors and processors. Building physically intelligent robot bodies requires a different manufacturing ecosystem, rooted in advanced materials and biomechanics, which is not yet mature enough to operate at scale.

When a robot’s hardware already looks so impressive, it’s tempting to believe the next software update will solve any remaining issues, rather than undertaking the costly and difficult task of redesigning the body and the supply chain required to build it.Autonomous bodiesThis challenge is the focus of mechanical intelligence (MI), which is being researched by numerous teams of academics around the world, including mine at London South Bank University.

It derives from the observation that nature perfected intelligent bodies millions of years ago. These were based on a principle known as morphological computation, meaning bodies can perform complex calculations automatically. A pine cone’s scales open in dry conditions to release seeds, then close when it’s damp to protect them.

This is a purely mechanical response to humidity with no brain or motor involved. The tendons in the leg of a running hare act like intelligent springs. They passively absorb shock when the foot hits the ground, only to release the energy to make its gait stable and efficient, without requiring so much effort from the muscles.

Hare today …Colin Edwards WildsideThink about the human hand. Its soft flesh has the passive intelligence to automatically conform to any object it holds. Our fingertips act like a smart lubricator, adjusting moisture to achieve the perfect level of friction for any given surface. If these two features were incorporated into an Optimus hand, it would be able to hold objects with a fraction of the force and energy currently required.

The skin itself would become the computer.MI is all about designing a machine’s physical structure to achieve passive automatic adaptation – the ability to respond to the environment without needing active sensors or processors or extra energy. The solution to the humanoid trap is not to abandon today’s ambitious forms, but to build them according to this different philosophy.

When a robot’s body is physically intelligent, its AI brain can focus on what it does best: high-level strategy, learning and interacting with the world in a more meaningful way.Researchers are already proving the value of this approach. For instance, robots designed with spring-like legs that mimic the energy-storing tendons of a cheetah can run with remarkable efficiency.

My own research group is developing hybrid hinges, among other things. These combine the pinpoint precision and strength of a rigid joint with the adaptive, shock-absorbing properties of a compliant one. For a humanoid robot, this could mean creating a shoulder or knee that moves more like a human’s, unlocking multiple degrees of freedom to achieve complex, life-like motion.

The future of robotics lies not in a battle between hardware and software, but in their synthesis. By embracing MI, we can create a new generation of machines that can finally step confidently out of the lab and into our world.