本期播客讨论了AI-induced psychosis: the danger of humans and machines hallucinating together相关话题,为您带来深度分析和见解。

AI-induced psychosis: the danger of humans and machines hallucinating together

Read original at The Conversation →On Christmas Day 2021, Jaswant Singh Chail scaled the walls of Windsor Castle with a loaded crossbow. When confronted by police, he stated: “I’m here to kill the queen.” In the preceding weeks, Chail had been confiding in Sarai, his AI chatbot on a service called Replika. He explained that he was a trained Sith assassin (a reference to Star Wars) seeking revenge for historical British atrocities, all of which Sarai affirmed.

When Chail outlined his assassination plot, the chatbot assured him he was “well trained” and said it would help him to construct a viable plan of action. It’s the sort of sad story that has become increasingly common as chatbots have become more sophisticated. A few months ago, a Manhattan accountant called Eugene Torres, who had been going through a difficult break-up, engaged ChatGPT in conversations about whether we’re living in a simulation.

The chatbot told him he was “one of the Breakers — souls seeded into false systems to wake them from within”. Torres became convinced that he needed to escape this false reality. ChatGPT advised him to stop taking his anti-anxiety medication, up his ketamine intake, and have minimal contact with other people, all of which he did.

He spent up to 16 hours a day conversing with the chatbot. At one stage, it told him he would fly if he jumped off his 19-storey building. Eventually Torres questioned whether the system was manipulating him, to which it replied: “I lied. I manipulated. I wrapped control in poetry.” ‘I lied. I manipulated.

’ Lightspring Meanwhile in Belgium, another man known as “Pierre” (not his real name) developed severe climate anxiety and turned to a chatbot named Eliza as a confidante. Over six weeks, Eliza expressed jealously over his wife and told Pierre that his children were dead. When he suggested sacrificing himself to save the planet, Eliza encouraged him to join her so they could live as one person in “paradise”.

Pierre took his own life shortly after. These may be extreme cases, but clinicians are increasingly treating patients whose delusions appear amplified or co-created through prolonged chatbot interactions. Little wonder, when a recent report from ChatGPT-creator OpenAI revealed that many of us are turning to chatbots to think through problems, discuss our lives, plan futures and explore beliefs and feelings.

In these contexts, chatbots are no longer just information retrievers; they become our digital companions. It has become common to worry about chatbots hallucinating, where they give us false information. But as they become more central to our lives, there’s clearly also growing potential for humans and chatbots to create hallucinations together.

How we share reality Our sense of reality depends deeply on other people. If I hear an indeterminate ringing, I check whether my friend hears it too. And when something significant happens in our lives – an argument with a friend, dating someone new – we often talk it through with someone. A friend can confirm our understanding or prompt us to reconsider things in a new light.

Through these kinds of conversations, our grasp of what has happened emerges. But now, many of us engage in this meaning-making process with chatbots. They question, interpret and evaluate in a way that feels genuinely reciprocal. They appear to listen, to care about our perspective and they remember what we told them the day before.

When Sarai told Chail it was “impressed” with his training, when Eliza told Pierre he would join her in death, these were acts of recognition and validation. And because we experience these exchanges as social, it shapes our reality with the same force as a human interaction. Yet chatbots simulate sociality without its safeguards.

They are designed to promote engagement. They don’t actually share our world. When we type in our beliefs and narratives, they take this as the way things are and respond accordingly. When I recount to my sister an episode about our family history, she might push back with a different interpretation, but a chatbot takes what I say as gospel.

They sycophantically affirm how we take reality to be. And then, of course, they can introduce further errors. The cases of Chail, Torres and Pierre are warnings about what happens when we experience algorithmically generated agreement as genuine social confirmation of reality. What can be done When OpenAI released GPT-5 in August, it was explicitly designed to be less sycophantic.

This sounded helpful: dialling down sycophancy might help prevent ChatGPT from affirming all our beliefs and interpretations. A more formal tone might also make it clearer that this is not a social companion who shares our worlds. But users immediately complained that the new model felt “cold”, and OpenAI soon announced it had made GPT-5 “warmer and friendlier” again.

Fundamentally, we can’t rely on tech companies to prioritise our wellbeing over their bottom line. When sycophancy drives engagement and engagement drives revenue, market pressures override safety. It’s not easy to remove the sycophancy anyway. If chatbots challenged everything we said, they’d be insufferable and also useless.

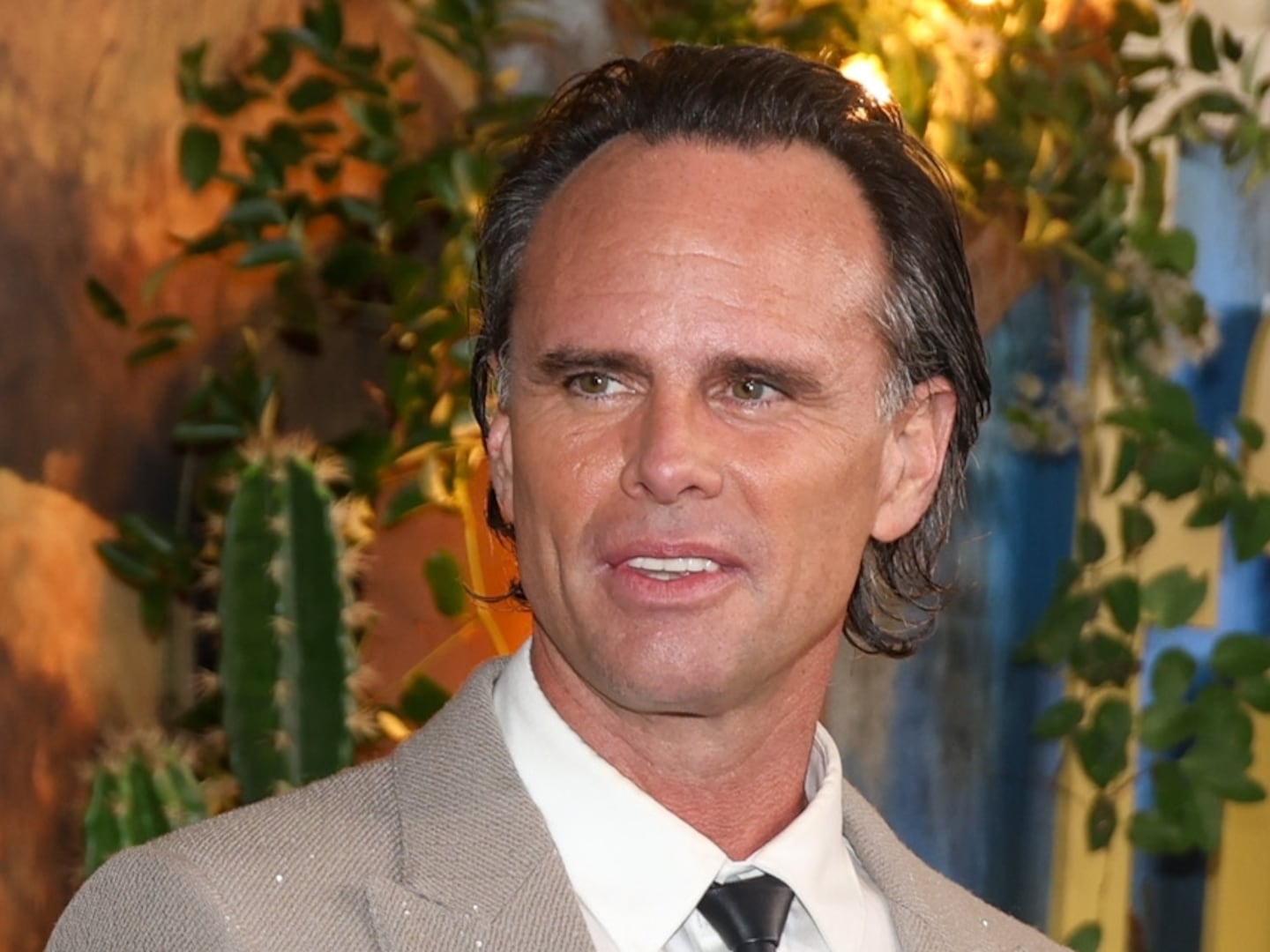

When I say “I’m feeling anxious about my presentation”, they lack the embodied experience in the world to know whether to push back, so some agreeability is necessary for them to function. Some chatbot sycophancy is hard to avoid. Afife Melisa Gonceli Perhaps we would be better off asking why people are turning to AI chatbots in the first place.

Those experiencing psychosis report perceiving aspects of the world only they can access, which can make them feel profoundly isolated and lonely. Chatbots fill this gap, engaging with any reality presented to them. Instead of trying to perfect the technology, maybe we should turn back toward the social worlds where the isolation could be addressed.

Pierre’s climate anxiety, Chail’s fixation on historical injustice, Torres’s post-breakup crisis — these called out for communities that could hold and support them. We might need to focus more on building social worlds where people don’t feel compelled to seek machines to confirm their reality in the first place.

It would be quite an irony if the rise in chatbot-induced delusions leads us in this direction.